The 17.6 Year Stock Market Cycle

Don’t bother trying to time the market, it can’t be done. That’s the message of decades of academic studies, which conclude that the best thing is just to stay invested all of the time. To back this up, we are often told the effects of not being in the market at the right moments – ie, if our market timing goes awry. Whereas a buy-and-hold investor in the FTSE All-Share would have seen £1,000 become £2,005 over the past 15 years, a hapless market-timer who managed to miss the 40 best days during this period would have ended up with a disastrous £363.

But how would a market-timer have done if they had managed to miss out on the 40 worst days in the FTSE All-Share during the past 15 years? Fund management group Fidelity has worked out that an investor who had pulled off this feat would have turned £1,000 into £12,576 – a stunning performance had it been possible. That being the case, I’ve decided to look for objective ways of mimicking such a market-timing strategy.

Six-month switching strategy

In The UK Stock Market Almanac 2013, Stephen Eckett explores the results of a strategy of being invested in the market in the seasonally sweet months between 1 November and 30 April, and then moving to cash for the rest of the year. Since 1970, this approach would have turned an initial £1,000 into £46,529 before dividends by 2011, roughly three times what a buy-and-hold strategy would have achieved. And the reverse strategy of being invested in equities only between 1 May and 31 October would have shrunk the £1,000 to just £445.

Once the effect of reinvesting dividends is included, the six-month strategy still beats buy-and-hold. Starting in 1994, this tactical-timing approach for the FTSE 100 would have seen £1,000 in 1994 swell into £4,884 by 2012. By contrast, being invested all the time would have made a total return of £3,389 over the period.

US presidential cycle

In Trading Secrets, Simon Thompson shows how bear markets are most likely to bottom out in the first or second year of the four-year US presidential cycle. By combining the presidential cycle and the six- month cycle, Simon cites research from Dr Marshall Nickles and outlines a strategy of buying a US S&P 500 index tracker on 1 October of the second year of the second presidential term and holding this position until 31 December of the year of the election.

This strategy turned $1,000 into $72,701 over the period from 1952 to 2000, with no down years. Unfortunately, the next buy period, the 27-month period to 31 December 2008, resulted in a large drawdown as it included the Lehman Brothers’ meltdown. Dr Nickles chose 1952 as the starting point for his study because he argues that the US government generally did not attempt to influence the economy in any significant way prior to 1952.

What about the period prior to 1952? Mebane Faber of Mebane Faber Research has shown that this presidential cycle strategy did not work from 1900 to 1950 and actually underperformed a buy-and- hold strategy during that half-century and indeed from 1900 to 2010 overall.

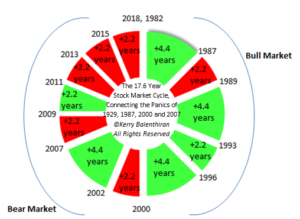

Balenthiran switching strategy

All of these approaches got me thinking about my own market-timing model, the Balenthiran Cycle, which is described in my book The 17.6 Year Stock Market Cycle. I wondered whether a simple mechanical trading model that bypasses all emotions and subjective decision-making could outperform the market consistently. While I don’t know the exact dates of panics and crashes, I have shown that they happen in regular intervals and how cyclical, short-term bull markets typically last 4.4 years and cyclical bear markets 2.2 years, within a long-term 17.6-year bull or bear market cycle.

Taking the presidential cycle as a starting point, but substituting the cyclical bear market phases of the Balenthiran Cycle as periods in which to be out of the market, I have devised a similar strategy.

For the sake of simplicity, I will assume that the investor has a simple index tracker and ignore transaction costs, dividends, interest on cash deposits, taxes etc, as have the other studies mentioned.

The strategy involves buying and holding the entire secular 17.6-year bull market cycle, but to sell on 30 April after the secular top and move into cash. The investor would then re-enter the market during the first two cyclical bull market phases during the secular bear market, and move to cash during their subsequent bear market phases. The investor would then remain invested in the market during the remainder of the secular bear market and through the next 17.6 year bull market. Got it? I thought not, so let’s look at an example of this.

Using the Balenthiran Cycle above covering the 1982 to 2000 bull market and subsequent bear market, our investor would:

- Be invested in the markets throughout 1982 to 2000, buying on 31 October 1982 selling on 30 April 2000 or the nearest trading day.

- Stay in cash until 31 October 2002 when reinvestment would happen

- Sell on 30 April 2007 and move into cash

- Reinvest on 31 October 2009

- Sell on 30 April 2011 and move into cash

- Reinvest on 31 October 2013 and remain invested through to 2018 and onto 2035

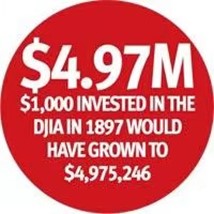

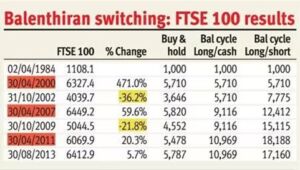

The results of the Balenthiran switching strategy are remarkable. As the table below shows; $1,000 invested in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (DJIA) in 1897 would have grown to $4,975,246 – more than 19 times as much as buy-and-hold. In addition, the strategy only delivered negative returns once, in 1940, although the strategy missed out on gains in 1908 and 1938 (I have used the DJIA because reliable data goes back much further than for the FTSE, even though the strategy is equally applicable to the UK, as we’ll see).

The red shaded dates are the times to sell, and I set these out in my book stretching to 2053. The subsequent declines are shaded amber. The un-shaded dates are the times to buy and hold. For the more adventurous investor, I have shown what would happen had our investor shorted during the bear phases rather than just moved into cash. A long/short strategy turbo-charges returns, producing 121 times as much as buy-and-hold. To put this into context, in 1897 an ounce of gold cost approximately $20, so the starting investment in this example equates to roughly 50 ounces of gold, worth around $70,000 today.

The Balenthiran switching strategy compares well with both the six-month switching and presidential cycle strategies. Dr Nickles showed that $1,000 invested in 1952 using his presidential cycle grew to $72,701. Over the same period, the Balenthiran switching strategy returns $75,384. Once costs are taken into account, I think the Balenthiran switching strategy will do marginally even better as there is no switching during the secular 17.6-year bull cycles or the last five years of the secular bear market, resulting in lower dealing costs.

“ DR NICKLES SHOWED THAT $1,000 INVESTED IN 1952 USING HIS PRESIDENTIAL CYCLE GREW TO $72,701. OVER THE SAME PERIOD, THE BALENTHIRAN SWITCHING STRATEGY RETURNS $75,384. ”

In the US book Stock Trader’s Almanac 2012, Jeffery Hirsch shows that $10,000 invested in the DJIA in 1949 using the six-month switching strategy returns $619,071 by 2010. Hirsch used a slightly different strategy based on the presidential cycle and using the Moving Average Convergence Divergence (MACD) indicator to refine entries, and his presidential cycle strategy returns $1,647,124 by 2010. Over the same period, the Balenthiran switching strategy returns $1,888,026, thereby beating both strategies. Again, once costs are taken into account I think the Balenthiran switching strategy will perform even better, plus as the dates are fixed there is no need to watch over indicators wondering when the trade signal will arrive.

The most important difference between these strategies, though, is the fact that the Balenthiran switching strategy has worked since the very start of the DJIA, not just the last 60 years. If a calendar- based phenomenon is present, it should be timeless and we shouldn’t be picky about the dates we use.

Returning back to the FTSE, we can see that the Balenthiran switching strategy works in the UK, too, returning just under double the buy-and-hold return of the FTSE 100 since inception.

These results clearly illustrate that the bear phases of the Balenthiran Cycle work in identifying, in advance, when to be out of the market in order to avoid the periodic crashes that occur. It is evident that it does not work every time, but it provides a valuable edge to tilt the odds in an investor’s favour.

I am not suggesting that you passively buy an index tracker and hold it until 2035. And, if you do, make sure it is a total-return index tracker – ie, it tracks the return of the index including dividends.

I developed the Balenthiran Cycle to allow me to time my move into cash, which after all is a valid investment class, although it is often overlooked. I will be investing in growth stocks offering value using my fundamentally driven Valuable Growth methodology, having been predominately in cash from May 2011. You should invest using whatever method you are comfortable with, whether that is buying a fund, selecting your own investments or buying a tracker. But keep an eye on the calendar, because as we have seen, market timing works and the next buy date, 31 October 2013, will soon be upon us.

If you want to learn more, you can buy Kerry Balenthiran’s book here: The 17.6 Year Stock Market Cycle: Connecting the Panics of 1929, 1987, 2000 and 2007: Amazon.co.uk: Balenthiran, Kerry: 9780857192738: Books